- Home

- Espriu, Salvador

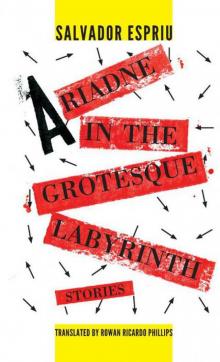

Ariadne in the Grotesque Labyrinth (Catalan Literature)

Ariadne in the Grotesque Labyrinth (Catalan Literature) Read online

ARIADNE IN THE

GROTESQUE

LABYRINTH

SALVADOR ESPRIU

Translated by Rrowan Rricardo Phillips

Contents

Cover

Title Page

A Note on the Text and the Translation

The Young Man and the Old Man

Little-Teresa-Who-Went-Down-the-Stairs

Psyche

Nebuchadnezzar

Death in the Street

German Quasi-Story of Ulrika Thöus

Nerves

The Rise and Fall of Esperança Trinquis

First and Only Run-In with Zaraat

Magnolias in the Cloister

Myrrha

On Orthodoxy

The Heart of the Town

Hildebrand

Thanatos

The Figurines of the Nativity Scene

The Beheaded

Vulgar History

Mama Real Lylo Vesme

Prologue to the Devil’s Ballet

My Friend Salom

Crisant’s Theory

Introduction to the Study of a Small Giraffe

Topic

The Subordinates

Ghettos

The Literary Circle

The Conversion and Death of Quim Federal

English Quasi-Story of Athalia Spinster

Panets Walks His Head

French Quasi-Story of Samson, Rediscovered

Sembobitis

The Moribund Country

Copyright

A Note on the Text and the Translation

Salvador Espriu continued to add stories—six more in all—to the various editions of Ariadna al laberint grotesc that saw the light of day between the book’s first appearance in 1935 and the author’s death in 1985, a period which spanned the rise, fall, and aftermath of Franco’s dictatorship. The last of these stories, the statement-of-purpose tinged “The Young Man and the Old Man,” was inserted by Espriu at the beginning of the book: the last becoming first. Both in form and function the prefatory “The Young Man and the Old Man” is a far more faithful introduction to the temperament of this masterpiece of Catalan literature than my prosaic intrusion into your enjoyment of it could ever be. An introduction to Ariadne in the Grotesque Labyrinth could occupy four times the pages of this slender text; and you, reader, will feel at times as though you could use one; but Espriu is interested in your being—or at least feeling—lost, and in the threads that lead you toward feeling less so.

Ariadne in the Grotesque Labyrinth lifts the specious reality of the surfaces of Espriu’s world to reveal the awkward, kaleidoscopic reality that exists beneath it. Among modern writers, Espriu is the one who most abides by the inner logic of his own world-making. Hence, many of the lusciously-named characters who will appear in these stories (and subsequently re-appear, interrupting narratives seemingly at whim with a syncopated nonchalance) also appear in numerous other stories and poems within Espriu’s oeuvre. Similarly, the invented names of the locations in these stories will be unfamiliar to those new to Espriu’s work. They are as follows: “Sinera”, which is “Arenys” backwards—Espriu is from Arenys de Mar, a coastal town about an hour north of Barcelona; “Lavínia” for Barcelona; “Alfaranja” for Catalunya; and Konilòsia for Spain. This last place-name plays on the Catalan word for rabbit, “conill,” and the name given to Spain by the arriving Carthaginians around 300 B.C.: “Ispania”—“land of the rabbits.”

What is a grotesque labyrinth? The adjective evokes Valle-Inclán’s theater of the grotesque. As both style and ontology, the grotesque offers torment and tragedy to its audience within a torqued, feral sense of reality. An admixture, at its best, of pathos and irony, this grotesque work of art is a daedal refraction of what had once been assumed real; and in this sense it offers the possibility of hope to those willing to read through its reflection, its refraction, its torqued and necessary otherness.

However, Espriu’s labyrinth is not only grotesque, it is also allegorical, a place and structure conceived of as both condition and cure. Class lines are constantly crossed; every form of betrayal—even the betrayal of genre—looms; quietly, a bestiary builds; anachronistic slang and the Caló language of the Iberian gypsies perforate the text. There is much betwixt and between, harshness and smoothness, crudeness and elegance, nonsense and sense, a sense of feeling found and of feeling quite lost all at once in this wonderful book. There is a strong baroque tinge to Espriu’s prose, the pulse of which in particular rises and falls in such a way as to evoke a style both fashionable and unfashionable, historical and ahistorical, stern and yet welcoming to purple patches. I have tried to remain faithful to that pulse by producing something in English that is close to the tone and temperament of Espriu’s Catalan (and Castillian Spanish and gypsy Caló). For readers who find themselves lost as they read, I ask that you consider it part of the process of winding through the labyrinth; or blame the translator.

Two final notes.

I maintained the symbols [«] and [»] as they were prevalent throughout the text but for the most part distinguished in their use from quotation marks.

And finally, I would like to dedicate this translation to Jordi Royo Seubas.

The Young Man and the Old Man

This little book was begun by a twenty-one-year-old who didn’t get along well with himself and was pretty hard on everyone else. A sixty-one-year-old who fails to get along well with himself and attempts—from a distance—to understand everyone else has finished it, perhaps. Perhaps. Quite a few things, and not all of them adverse, have happened during the intervening forty years. Things that are, or should be, understood and remembered.

During that time this little book was remolded again and again, without end. Perhaps this effort wasn’t worth the trouble. No doubt the extremely tedious labor was in vain. But both the young man and the old man coincide in their affirmation that this, and all of the other works brought to life by the two of them—as well as those works (who knows?) that the old man may still have time to realize—are merely ephemeral tokens of a strange and difficult apprenticeship set within the perplex coherence of a labyrinth. And in this affirmation one would like to see, with a benevolent irony—an irony that seems rather grateful, from this vantage—a sarcastic skillfulness, the lightning rod of false modesty, when it merely reflects an uncomfortable, obsessive, and literal truth.

All the echoes of noucentisme and post-noucentisme that this little book contained, that could have been pointed out here and there, have been extinguished, bit by bit, in systematic order. If some trace of them remains within the diction and syntax, it’s been kept expressly for its grotesque clink.

It’s the same book, and yet, at the same time, another. The young man didn’t err completely; and it’s out of bounds to claim that all of the old man’s suggestions were right. Which is why the old man has maintained in his mind, and so often returned to, that first distant draft of the text. He preserves from it a certain ingenuousness more apparent than real; and he has eliminated whatever imprecise or coarse expressions it contained. The young man suspected, and the old man firmly believes, that anything can and should be said without falling head first into the sort of dull and jejune shoddiness that industriously seduces so many talented pens—the most indigestible leftovers from rhetoric’s waste bin.

Nothing in this book has been invented. Everything told in it happened, one way or another. The young man possessed, and the old man preserves, a precise memory, an ear and vision diligent and acute. But neither of the two has benefited, not even on the rebound, from the brilliant,

utterly enviable subtleties of the imagination.

This little book forms an essential unity. Thus, the hypothetical curious reader should read these prose pieces according to the very deliberate order in which they appear. Some short stories here serve to round off and stress the meanings of others, as well as functioning as links. They also present clear situations and characters that will be the objects of other stories.

The young man has vanished, of course. His heir, the old man, is still here. But the only award he’s attained is a glacial serenity. His profits are such that he’ll never complain.

«Let’s leave him cold, if not lukewarm,» Senyora Magdalena Blasi said, toning things down. «And let’s not waste time trying to figure him out, because we’d immediately raise his temperature, with a consequent alteration of the costly product.»

«The old man desires no distinction, doesn’t want to belong to any institution, to any organization or faction,» Salom the ventriloquist intervened.

«Either of them now opposed to the genuine interests of a country that cannot allow itself the foolish luxury of any type of dispute,» lectured the acknowledged patriot Carranza i Brofegat.

«The old man,» continued the ventriloquist, «does not want to figure on any list, nor in any ambiguous, sentimentalizing document. He wants neither to collaborate nor to go anywhere. He doesn’t want to be manipulated any longer by alleged—and more often than not indelicate—affections, those pressures to which he was forced to yield himself with mild but always lucid contempt.»

«He’s played it off long enough,» Senyora Magdalena Blasi responded.

«The game, if indeed there has been a game,» Salom started up again, «is forever over. Before the old man lies the rough slope of his duty—either uphill or down. And he’s taken on tasks that he’ll seek to complete, whether or not they’re to his liking.»

«If the old man tends to swell up, I can’t deny that he cares,» added Senyora Magdalena Blasi.

«The old man no longer wishes to present to the public,» said Salom, «even a single commodity that is someone else’s—be it more or less intelligent, inspired, sophisticated, or authentic. He does not want to judge anyone, or respond to polls, or suffer through any more absent-minded, reiterative, inelegant, monotonous interrogations . . . unless they are, for example, a matter for the authorities or for a judge. He is in neither the physical nor the moral condition to maintain any type of regular correspondence. If he does not love very much and does not hate at all, then he profoundly respects everyone. In exchange he requests that his solitude be respected, without exception. He supposes that is not too much to ask.»

«Yes, it’s definitely too much to ask!» murmured Senyora Magdalena Blasi, between yawns. «And he’ll have to readjust—by force, if you please—his plans. On the other hand, this gloomy old man would willingly thumb, in his premature niche, through newspapers and magazines.»

«Let’s see if these brief paragraphs,» psalmed the ventriloquist, «excluding all kinds of haughtiness without, however, excluding the opportunity for it, end up being intelligible. For this skeptical man, whom neither gold nor terror nor any flattery could buy or soften, was taught according to norms of rigid courtesy no longer incumbent. And he has been quite vulnerable, thanks to this gross defect in his education. He has liberally given away his time, but can no longer afford to lose even a mere morsel of it. He owes only that to his conscience—which, if it didn’t seem pretentious, would at least qualify as strict, though also independent and free.»

«He’s a scaredy-cat and a softy!» Senyora Magdalena Blasi yellowed. «Everything, leaving aside the eternal mysteries of inflation, has a price,» she smiled, with good reason. «If the old man exalts himself it’s a trick of age. But he’s not so old. He exaggerates. I’m older than he is,» Senyora Magdalena Blasi impartially confirmed.

«Along the curve of the biological and the essential, nothing is fixed,» stated Doctor Robuster i Tramusset, with blanched eyes.

«The feedback from my naked words,» concluded Salom, «does not by any means have to affect this tired man incapable of deception and self-pity. If he wanted, he would pray for those who are his friends, and those who are not his friends alike, to be saved.»

«These precautions won’t stop them from skinning him,» said Senyora Magdalena Blasi scornfully, as she receded.

In the little book discussed above, along with a number of dialogues and monologues, oddities and extravagances, there is some gipsyism and a very few neologisms and semantic leaps, and the vocabulary and discourse are subject, not without restrained rebellion, to the dictated and codified laws and lists of the Institute of Catalan Studies, some of whose pressing rules will have to be modified and revised bit by bit. We find ourselves today between two fires: on the one hand a rigid and paralytic purism; on the other an irresponsible and inadmissible patois. Perhaps one will have to insist on searching, between extreme and extreme, for the equilibrium of a middle ground. The man who writes these lines ought not to instruct anyone, does not want to instruct anyone, nor can he instruct anyone. Because he has no authority. Because—if by some tactical miscalculation a speck of it is attributed to him—as everything has been sung, recited, or told, and everyone has forgotten everything, nothing should have to be repeated. Because the old man has learned that «many words that have been lost will be born again, and many more now honored will be lost.» Because he understood, through his dangerously intimate contradictions, that «the language of art’s future is always an unknown language.»

S. E.

Barcelona, 25 July 1974

Many years ago, Ariadne guided you, for half an hour, through a simple but singular labyrinth. She went ahead of you. You walked among odd voices and shapes. If you felt faint you could sit down in a peaceful corner of your own choosing. You didn’t have to encounter the Minotaur. The labyrinth was insignificant, harmless, for tourists. When you tired, diligent Ariadne would attend to you and, at utter peace, show you the point of departure. But if she sensed you were feeling bold, she benevolently left you the illusion of having discovered the way out on your own—though without her you would have been lost. Ariadne was discreet; she barely spoke, insinuating the path for you to follow with a soft gesture. Ariadne was modest; and I advised you how best to reward her: you had to invite her, once she got off work, to tea and a dance. If you were to her liking—educated in Germany, Ariadne, was a romantic—and you requited the feelings of that affectionate girl, then it was good to remember that Naxos was always at hand. Upon waking, the sleeping beauty complained of the silence, but was soon consoled: just off the coast, Dionysus gathered Ariadne’s destiny. Hard times followed nevertheless; and that destiny was ruined, as was mine, as were perhaps all of ours.

Little-Teresa-Who-Went-Down-the-Stairs

To Maria Aurèlia Capmany and Llorenç Villalonga, in homage

and with the promise to never revise this story again.

I

«It doesn’t count, it doesn’t count yet: you’re looking. You have to close your eyes and you have to turn your back to us and face toward Santa Maria. But you have to focus on the route first, it goes through Carrer dels Corders, past Carrer de la Bomba, Behind-the-Bakery, Carrer de l’Església, and the little square. No streams, because we’d sink; and the route is long enough as it is; if we tried it we’d never get it done, and besides it’s really tiring. The rectory: the safe wall—okay? Now now, we don’t need to cheat. Teresa stops—come on!—we run. It doesn’t count: she was peeking. Teresa, kid, I already told you that you have to turn your back to us and face Santa Maria. If you do that then you don’t have to close your eyes, but you can’t move till we yell out. Let’s see—do you guys understand me? Yeah, we’ll take Carrer de la Torre; let’s go over everything one more time. Not through the stream since the sand can trip you up. You’re asking us to count again? We counted earlier, Teresa. That’s not good enough? We’re wasting time! It’ll get dark, they’ll bring the boats back in and we w

on’t have even begun to play. What? The Panxita is coming back from Jamaica? That’s no big deal. My father went further, all the way to Russia even. He came back with a fur coat and hair everywhere: he looked like a bear. My father always tells the story about when he went to give thanks to Friar Josep d’Alpens—who was on the pulpit—for the safe trip back, and he greeted my father with curses, like he was the devil. Come on, are we going to play or not? It’s like yours was the only frigate in the world. Ai, kid, you’re so stubborn! Let’s count—and no complaining about whoever gets picked. Macarrò, macarrò, xambà, xibirí, xibirí, mancà. It’s you again, little Teresa; that’s tough. Everybody spread out! You’re limping, Bareu? Wait up, guys. Bareu is limping. Does he get special rules or does he guard the area? Okay, then he helps keep an eye on it. Don’t complain, little Teresa, you won’t be doing the seeking by yourself. Come on. At last. Hey, facing the wall! Limping or not, if Bareu’s the gatekeeper it’s going to be impossible for us to get near the rectory. Who screamed “ready”? No, Teresa, no, we haven’t hidden yet. Don’t come down the stairs, little Teresa. I said don’t come down the stairs—some good-for-nothing shouted out too early. Excuses? Me? A troublemaker? Me? Because I see I’m caught? You really don’t want to play, do you! And you’re mad that you have to stop, that’s it. Don’t come down the stairs, you hear me? Don’t come down. Fine, get worked up about it. Sure, go ahead and run after me. I give up.»

Ariadne in the Grotesque Labyrinth (Catalan Literature)

Ariadne in the Grotesque Labyrinth (Catalan Literature)