- Home

- Espriu, Salvador

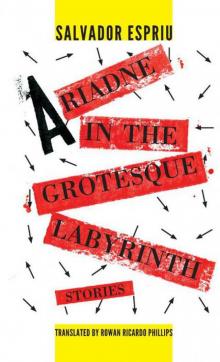

Ariadne in the Grotesque Labyrinth (Catalan Literature) Page 2

Ariadne in the Grotesque Labyrinth (Catalan Literature) Read online

Page 2

II

«You haven’t seen them? Boy, where are you coming from? They’ve been back since yesterday! It was a noble three-month voyage this time, through the Baltic, then through Germany, Switzerland, Milan, Venice, and Florence—overland, of course. They left the Panxita in Danzig. It’s strange—they didn’t have to go to Italy. Their route was solely sea-bound: a commercial route. They must have persuaded the captain to change it to a pleasure trip, a romantic voyage. Their father gives them everything they ask him for. Today they’re radiant, restrained and tireless. They brought back mountains of magnificent objects: glassware from Trieste, porcelain from Capodimonte, marbles, silks, medallions. They were seen in Fiesole with Vicenç de Pastor, or he went there to find them, because he loves Teresa. I suspect his return wasn’t very triumphant: he’s glum, his confidence has sunk. Yes, they’re very pretty girls; and Teresa is more beautiful than Júlia, no? No, I don’t buy that: Teresa is more beautiful. Above all, since they’ve returned I’ve noticed a splendor in her eyes, a distant light captured, a joy hidden and revealed at the same time. Júlia is more delicate. Her mother died of tuberculosis, keep that in mind, and that was a tremendous blow to the captain. I think he’s in Trinidad now, surrounded by blacks and white trash. He married a Creole woman, perhaps she was even mixed; they have a wretched child—a hunchbacked daughter—and I believe they’re going through lean times. They’re coming closer. Look how they come down the church’s steps, barely brushing them. Teresa is exquisite—you can stick with Júlia. Go ahead and laugh about it, go ahead; but they look like duchesses. And this afternoon, at the arbor dance, they’ll be queens.»

III

«Don’t greet Teresa. Don’t greet her. She doesn’t see anyone. How she’s changed; she used to be so happy! It’s that there’ve been so many blows, one after the other. After such slow agony, after fighting courageously for so many long months, Júlia died. The day after her death, the Panxita got stuck in the mouth of the Rhône. No, no, it won’t be so great a financial loss, since Vallalta’s rich; but he loved his frigate so much. Since it sank he’s hated sailing and hasn’t set out again. He just passes his days on his estate—the “Pietat”—contemplating the sea at a distance, surrounded by trees and books. He was so strong before, but now he is a dithering, decrepit old man. No more stories of sea adventures from him, he’s lost his memory. What a man he was! They say that last century, in his younger days—thrill-seeker that he was back then—he even took part in Barceló’s expedition against Algiers (although perhaps these stories don’t add up), and after he was everywhere: Iloilo, Mexico, the Nicobar Islands, Newfoundland, Odessa; but now the captain wants nothing more than to die surrounded by the peace of his groves. His daughter looks after him, keeps an eye on him. Yes. Teresa is a woman of maybe forty years, maybe more, and Vicenç de Pastor is still waiting for word from her; but Teresa loves no one. Don’t greet her, it’s useless, she won’t see you. She descends the stairs lifelessly.»

IV

«Pay attention to how she descends the stairs. What a woman! Lady-like, slow, measured, and at the same time quick, at the pace no doubt of some practitioner’s school, some lost style. Yes, Teresa is very old, you already know that; she’s my age. Do I remember? We played together so often, right here in this square: tag, tic-tactoe, planted soldier, leapfrog. All of that’s way in the past now. The town seemed bigger to us back then—immense, richer in color and character. Running around we always discovered a hidden, new corner. Each afternoon, we waited in the sand for the boats to dock and the occasional return of some sailboat from America or China’s remote seas. My father was a pilot, too, and he’d go as far as Russia, crossing frozen waters, skirting small glaciers. He’d return dressed in furs, like a bear; he scandalized the church with such luxury. Everything happened. One day, in the early evening, we plunged into the damp canebreak, chilled by the shiver of forbidden adventure. We groped our way forward, and it spun us round with the premonition of miracle. There was perhaps a cobweb of fog over Remei and a witches’ storm-cloud at its heart, above the Muntala. And upon returning we told our grandparents about our run-in with a ghost. Everything happened. We grew up, and I married. Teresa and her sister Júlia, who died from tuberculosis years ago, traveled with Captain Vallalta in the Panxita. Later, the frigate sunk, and a little while afterward Júlia and the old man died. And there you have it. Teresa passes right by me without even a glance, with her hunchbacked niece—with her dog’s shadow—behind her, she brushes up against me and doesn’t even look, and my family is at least as old as hers, and I have to address her like I was an artisan. Everything happened. Teresa is a sad, old woman. She doesn’t know how to laugh. And the town seems to me, and to her as well, I’m sure, so small, so empty and ramshackle! And way back when, we imagined it limitless, as if in a cloud. Carrer de la Bomba, Rera-la-fleca, Carrer de la Torre. Teresa used to come down the church steps so quickly. And now look at how she descends them. Still so ladylike, nevertheless—with a lady’s step.»

V

«You’ll say, isn’t the box of the “Frigata” made of good wood? And away she goes—the niece is stingy, come on now, but she wouldn’t skimp one cent on a detail of such supposition. They carry the same blood from head to toe, and she won’t expose herself to people’s harsh tongues. Look, from caregiver, or worse, to executrix: the paths of life. Senyor Vicenç de Pastor is so hunched over! He looks like an axiom. Don’t fool yourself, he’s so old and so isolated, and they say he always loved her . . . who knows. Yes, quite a crowd; you don’t see this sort of spectacle so often: women like the “Frigata” don’t die every day. Uf, very rich—calculate it to be at least two hundred thousand gold pieces and you’d probably be short. All that money, all for the humpback. Ai, no, daughter, no, she’s of no interest to me. God gave me a straight back and good health. I prefer that. Let’s leave it at that! Look at how they surround her. Yesterday they were practically driving her off with the cracks of their whips; and today, look how they kiss up to her. Everyone is there: bouncy Bòtil, Coixa Fita, Caterina, Narcisa Mus. These last three ladies, all three of them, wrapped old “Frigata” in a shroud, because Paulina—the niece—wasn’t capable of doing it, and they’re already passing her the dish, the evil schemers. Do you know what Narcisa told me? Come here—while they were searching for her mantilla they found a box with some blond locks in it and the portrait of a man, the portrait of a young, tall, strong man. And, hold on, there was a name at the bottom; a strange Frenchie-sounding name. And no one ever suspected anything, given how much she traveled! And she was so hard, so proud. She wouldn’t say hello to godmother—my godmother—because, God forgive her, she was poor; even though they played together as children. And now you see it: one, behind your back. Let’s go. It’s all just guessing. The thing is, maybe she never did anything wrong. Hush, they’re bringing her down now. She must be heavy, and these stairs are narrow; I hope they don’t slip. The wood is expensive, no doubt about it; it’s expensive, I already told you that. The pallbearers are sweating, shameful, just look at the way they’re sweating. Let’s see if they crack it open at the bottom of the steps.»

Psyche

«Slowly, the path of a hydrosol to a hydrogel or, if you’d prefer, the coagulation of a colloid. Or perhaps he died, he, the beloved, wretched body. Perhaps only the reflection of him on the waxy surface: conscience. And then I found myself—lost within an alien, difficult, bizarre geometrical realization. And I understood that I’d never influenced him. He had lived, and I, sacrificed to him from the beginning, indispensable ingredient, so that he could walk under the sun. And now again I’ve found myself—and my, have I found myself! I started, I started from I don’t know where—light, idea—and I found, again, my form. Specifically: one, shall we say, very small butterfly; yes—that’s it—a miniscule moth. With a voice. I can’t place it inside, but rather more like all around, behind: I can’t pinpoint it. I’m so young, I’m familiar with so little! I think of him, like him, so m

uch still! I’m so scared of the black cat! . . . Come, come! . . . Radiant voice, at least. Inside, outside, and all around.

»I’m a moth: a small, a miniscule moth. Hands, paraffin? My voice, you know? And of “he,” of “I.” And now Pròspera has turned, perhaps because she heard him, and runs hastily toward the candles. The candles tremble under the demon’s breath. The curtain of fire doesn’t permit . . . doesn’t permit the beast to pass. The cat keeps an eye on me, and moves, noisily, its paws. Don’t blow out the flame! All I, him, stretched out, motionless, the belly swollen, juicy. Prior tasks . . . operation . . . to rot . . . Succulent. Pròspera contemplates him. How fat! Old, debaucherous woman, Pròspera. How she hates you, old man! Thirty years: always with Pròspera. And he kept his eyes fixed on her, as a hobby, to—how can I put it—to scare her . . . a little. But he failed, because Pròspera knows that his company won’t be solicited, that she can’t touch. She stayed up with him, snoring, the greedy beast kept an eye on him. The candles burn so high! . . . The mirror, covered . . . And then I found my way in the darkness and slipped through its half-opened mouth. The closest candle drew me in. The candle . . . it swept away the visible breaths. And I should have freed myself from the dominion of the gluttonous pawed beast. Paws! . . . I’m so scared of the black cat!

»But the candles shone high, magnificent candles, and they cleared my path. I saw myself, I saw it. Moth, body? It suffered so much, I suffered so much! Lean, skeletal, a coagulated colloid: that’s all. All? Who will redeem the vulgarity of things? . . . Pròspera. How ugly! Real. Without secrets, infinitesimally localized. Don’t snore. Don’t make any noise. I’m a moth. A miserable, minuscule moth. I want to get outside, out of the darkness. Make no noise. It hurts. I’m a moth. A voice. A thought tied to instincts. An ex-life. Pròspera snores, and her panting distances the gloomy path, the cat spies the path of gloom. But the candles are so high! And I so love this body, I love it so! I cannot abandon the circle of fire, the rotten circle, the ex-life. I cannot, because they see me, you know? I swell. If I were smaller. If I were invisible . . . But they see me. He was generous, he was being vain, and I, for these characteristics, am condemned to be seen. A great moth: I swell.

»Pròspera awakens. Wake up, Pròspera! How ugly, how old, how yellow! She awakens, prays. But are you thinking, Pròspera, about money, about some bad stew, about stews, about the bed? She’s sleepy, it’s natural. He didn’t love her—that said, she looked after him, out of custom is how I’d put it to you all. Out of loyalty to that image, so ancient, of thirty years ago. You and me, him, Pròspera, thirty years ago. The mirror, covered. Pròspera is dry, lacks imagination. Just, just the custom, a ring, some words, a buzz, an echo. That’s all.

»Pròspera yawns. She’s tired. She looks and looks again at the bed, she prays. She fell asleep lightly thinking of the white sheets, of the money. He rotted away unnoticed. The beast, a glutton, spied. The candles burned. I think in circles. How am I going to slip out toward the darkness without falling to the empire of the cat? Ai, ai, ai. Pròspera has seen me. What is that? A moth, a moth, a moth, Pròspera! Ai, ai, ai, you trap me, you gather me in your hands! Will this, perhaps, be the way? The way towards the darkness, far from the beast, from the candles, from Pròspera, from the voice, from the ex-life, toward that morsel of God . . . eh! . . . that which is my share.»

Suddenly, a clean hit: the common sound of one palm against the other. The voice stopped, a painting fell noisily from the wall, the hour chimed, someone turned on the lights, two of them, fervently faithful, had had an accident. «The stage machinery worked tonight for Saurimonda,» applauded young Estengre. «As I’ve understood it, this Pròspera knows where she has her right hand and her left, and that’s it,» Uncle Nicolau Mutsu-Hito approvingly said. «And she doesn’t stand for moths eating holes in her clothes. I’m smashing any moths that come within reach too,» assured Senyora Magdalena Blasi.

Nebuchadnezzar

To Justi Petri, Arcadian of Rome, studious, in process,

from biblio-babylonic problems.

I

His father’s side of the family were people of the earth, like all of you, like me, like all of the citizens of Konilòsia. As for his mother’s side, they returned to the earth. Nebuchadnezzar Puig was his name. He inherited the «Puig» from his father. The «Nebuchadnezzar» from the devout affection directed at him by his great-grandmother, a pious Englishwoman. The pious branch of the family had fallen into an abundant current of Catholicism, and amidst this fervor arrived Nebuchadnezzar, a man of good sense, steeped in positive indifference, whose holding pattern held until his good death. The war of ’14 found him working as a cobbler—and he made a living out of it. That story flew over his head, neither enriching him nor, for that matter, refining him, and Nebuchadnezzar failed to take advantage of the unique opportunity before him to be heard merely for the sake of the money he made, as would a man of culture and pedigree. Like those of his town, he had, however, good sense. He possessed concrete ideas about life, love, and changes of weather—and he made a living out of it. Touching upon love, he was always partial toward making it legal through marriage—any affirmation to the contrary is inaccurate—but he didn’t give getting it right much of a chance. It frightened Nebuchadnezzar to see his friends embark on that adventure so easily.

«When I do it! Don’t rush me. Yeah, look at him! After, to the gallows and crack! A laughing stock, right? Me, dangling, hunted down, no doubt. No way, don’t complicate things for me. When will I be better off than I am now?»

It was true. Nebuchadnezzar was happy, he prospered before the Lord and scoffed at pointed questions. And everyone envied him and hailed his perspicacity. And he was taken for a fearsome man, a man of experience.

«No, certainly not, they fool you. They’re not going to snare me.»

Until he ran into Evangelina. And they wed.

II

Six months later, Evangelina gave birth to a daughter. And all in Nebuchadnezzar’s spirit was desolation. And he cried and promised a bloodbath, an exemplary vengeance. And he did nothing. He thought it over calmly, requested censure of opinion, and found out whose the child was; it turned out the father was a powerful man. Nebuchadnezzar accepted the requisite smearing and took the child to be baptized. Was it permissible to decide to do anything else to innocent flesh? The flesh was redeemed by gold or holy water. They gave her the name «Candelera.»

The truth, however, instantly made its way around the humid, dirty town with its worn-down geometry of doors and sunless windows. And Nebuchadnezzar was the laughing stock of his neighbors who had, until yesterday, admired him. He saddened, quit his job, and started going to the bar. And, already a professional drunk by this point, he took to screaming at all and sundry his ignominy: that he had lost his cool and his glory, his famous perspicacity. That he no longer earned an honorable living.

«They bought me. I’m a bought man and I say nothing. That’s why I didn’t throw them out of my house. They pay me.»

They called him, for the likeness, “Widow Belly.” A Plautian yelled out to him:

«You’re lost. You don’t deserve the name “Nebuchadnezzar.” It’s too long. I’m going to call you just “Neb.” I’ll save some spit. Crisis, boy.»

He assented, filled with sadness:

«Yes, I am lost. Call me “Neb.”»

Work complete. Justice done. Degradation. He already is, and always will be, Neb Widow Belly; or, shorter still, Neb.

III

Senyor Pepa Sastre, potentate, expanded the Neb family with two more members: Oliva and Perpètua. Males weren’t born of that happy union, and so Senyor Pepa Sastre, who wanted an heir, tired in the long run of maintaining Evangelina and her unsatisfactory lineage and withdrew almost all of his financial assistance. He was a refined and sentimental man. A man in possession of these qualities never goes as far as to completely break old ties. From a distance Senyor Pepa Sastre kept an eye on the physical and ethical upbringing (Evangelina

had turned decadent and flabby) of the three little girls, which was guided along the right path by good Neb, whom they gratefully loved like a father. After knowing their choice, Senyor Pepa Sastre could only sigh. «They’re doing well,» he said meditatively. «They are young, pretty, strong. May they gosh darn get to work!» Senyor Pepa Sastre, ever the patriot, was a solidly doctrinaire and sufficiently rigorous liberal.

Meanwhile, Neb was getting older. Everything was ending for him in this life. God, who chokes but doesn’t exactly strangle, had pity on the guy. Neb was slightly redeemed from the little thing still dragging on the ground—from Senyor Pepa Sastre’s desertion—by the effort of his lucrative daughters. He had been prudent and now he could pass entire days at the bar. The old conjugal wound somehow managed to heal and, as tends to happen with old stories, it acquired prestige in the eyes of the younger generations (may the illustrious Petri take note that the war of ’14 did not ennoble poor Neb). His daughters would hurry about under his orders, and he was an expert in talking about it.

«May they always be good with money, praised be God.»

«They always are,» affirmed a meddler.

«Naturally. They tuck away coins, and so, God willing, they will be able to retire.»

Ecolampadi Miravitlles, a reformer riddled with quixotism, who visited all three girls and made no distinction among them, opined:

«Sibling love can sour an affair.»

«It is life’s path,» said Xanna the coachman, philosophically.

But, passing through, he said it in a language so dense that no one understood him.

IV

And Neb followed his life’s path in its entirety and arrived at the end. And he was cried for by Evangelina and watched over by Candelera, Oliva, and Perpètua, who took some days off to care for Neb. And, in dying, the tears of Pasquala Estampa, Cristeta Mils, and Pudentil·la Closa, neighbors, fell around him, and those, too, of Doloretes Bòtil, wing-wounded, so bouncy, and the sniffles of Esperanceta Trinquis, who was like a sister to him. And, in that supreme moment, the aides of Father Silví Saperes would not fail to be accounted for. His soul was freed, then, to its Creator. Comforted by religion, and by the praise of those who’d loved and respected him in life: everyone who’d dealt with him. And he was, upon leaving the valley, sixty-two years, three months, and a day or so old. And, now dead, they fit him in a coffin.

Ariadne in the Grotesque Labyrinth (Catalan Literature)

Ariadne in the Grotesque Labyrinth (Catalan Literature)